In the middle is Lyova Krichevsky, a Krasnaya Presnya foundry shop foreman Ц or maybe chief engineer. He is well preserved and quite recognizable. And behind Plaskeev is Zhenya Abelman (Khramov), who, alas, is no longer with us.

In the middle is Lyova Krichevsky, a Krasnaya Presnya foundry shop foreman Ц or maybe chief engineer. He is well preserved and quite recognizable. And behind Plaskeev is Zhenya Abelman (Khramov), who, alas, is no longer with us.There was another touching meeting in 2003 on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of our acquaintance in 1943, when we were 3rd graders in School є 61 after returning from evacuation.

Another detail of my life during the war suddenly comes to mind: up until the summer of 1946, I used to run around Moscow barefoot, even take the Metro in bare feet. It was absolutely normal back then. I am presenting a fragment of the well-known photograph by Yevzerikhin from 1940, in which you can see the barefoot Moscow boys of the pre-war years.

Another detail of my life during the war suddenly comes to mind: up until the summer of 1946, I used to run around Moscow barefoot, even take the Metro in bare feet. It was absolutely normal back then. I am presenting a fragment of the well-known photograph by Yevzerikhin from 1940, in which you can see the barefoot Moscow boys of the pre-war years.I recall that on Victory Day, May 9 1945, whether because it was the occasion of that great holiday or because of the lingering spring chill, I was in Red Square in a pair of slippers. I was almost trampled by the crowd, and the slippers got lost in the crush, so I came home barefoot again.

AbelmanТs situation was complicated by being charged with uncomradely behavior towards not one, but three women. The absurdity of such an accusation was underlined by Zhenya Plaskeev: УOne look at scrawny Abelman is proof enough that he couldnТt handle one, much less three, women.Ф

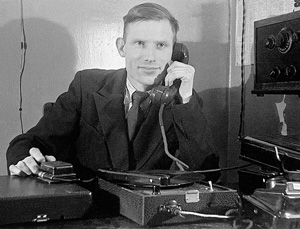

And in this photograph is the physics teacher, my dear Teacher, Sergei Makarovich Alekseev.

And in this photograph is the physics teacher, my dear Teacher, Sergei Makarovich Alekseev.An ardent radio ham, he helped develop such a passion for radio in me (and others as well) that it became not only my most consuming boyhood hobby, but my profession, and my destiny. A rare case of a teacher and a student becoming Ц I am not afraid to say Ц friends. We often visited each other at home. Later, when I was a college student in my third or fourth year, we bought a car together, a УMoskvich-104,Ф splitting it four ways (the others were college mates). Sergei limped noticeably; he had been handicapped since childhood, and simply needed a car.

We bought the car at a flea market next to the only car dealership in the city at the Bakuninskaya metro station, near Spartak Square. The dealership featured the УMoskvich-104Ф for 9,000 rubles, and the УPobedaФ for 16,000. The mysterious ways for how the many-year waiting list for this luxury item was formed were unknown to us. At the flea market, a moderately used УMoskvichФ cost us 10 000 rubles, Уregistration not included.Ф How we managed to collect enough money is beyond my capacity for storytelling. But hereТs an amazing thing: group ownership of the car never caused any conflicts.

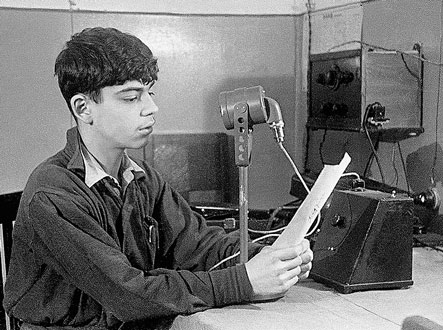

These photos were taken at the schoolТs radio center. I was its chief my last 1 Ц 1/2 years in school, and was very proud of this position.

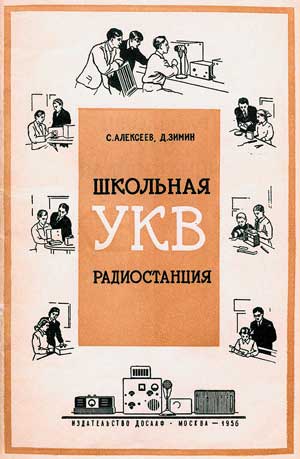

Funny, that IТve never mentioned this book in the list of my Уscientific publicationsФ which I regularly submitted at RTI for various evaluations and formal contests Уfor a replacement.Ф Towards the end of 1980Тs there were more than a hundred items on the list. It seemed as indecent to put a ham radio booklet on the list, as it would be to include an article printed in the school paper.

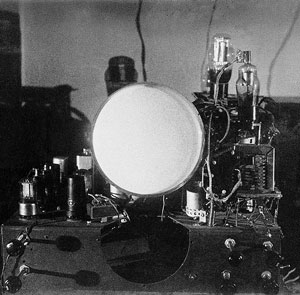

From my own ham radio creations, I canТt resist showing the miraculously unscathed photo of my hand-made TV set. I got it working around the year 1950. Our entire communal apartment gathered to watch it. There was a total of two TV sets in our whole building: the recently issued industrially-made KVN-49, and mine. With a little effort, I could probably determine the exact date when the first distorted images graced my TVТs screen: the movie УMichurinФ was on.

From my own ham radio creations, I canТt resist showing the miraculously unscathed photo of my hand-made TV set. I got it working around the year 1950. Our entire communal apartment gathered to watch it. There was a total of two TV sets in our whole building: the recently issued industrially-made KVN-49, and mine. With a little effort, I could probably determine the exact date when the first distorted images graced my TVТs screen: the movie УMichurinФ was on.

Television back then had only one channel and was broadcast from the Shukhovskaya tower at the Shabolovskaya metro station.

A few years passed, and a forest of TV antennas aimed at that tower sprouted on the roofs of the Moscow buildings. But at the time of my story, to own a TV was, as they say now, Уcool.Ф

Unfortunately, I donТt have photographs from that time illustrating my radio ham activities.

There were flea markets, at first at Paveletskaya, then in Koptevo, where the whole of radio-loving Moscow gathered on weekends (we had only one day off then Ц Sunday).

In the first post-war years, the whole neighborhood knew that a radio ham lived in the building. In the summer a speaker would be blaring from the open windows: УRio-Rita, It is rainingЕФ There were dances in the courtyard or in the street in front of the house; cars were rare then on Arbat bystreets.

Industrially-made radios, almost exclusively German-made war trophies, were rare then too. And then again, their speakers were only in 1-3 watt power range. A ham radio had an amplifier with two 6F6 tubes, and later even a 6P3 in the push-pull, add to it an outdoor speaker (RD-10, 10 W!) on the windowsill and Ц everybodyТs dancing! УYesterday my speaker was heard on Gogolevsky BoulevardЕФ Ц not for long, only until angry parents and neighbors came running.

The dance would go on to the sounds of softer music. As for me, I had never learned how to dance Ц my job was to change the records.

A school boy who was a radio ham would enjoy respect beyond his years on the part of, say, the chief electrician in the building. When the going was tough, the boy could teach him how to steal electricity (without it registering on the meter) with the help of a grounding wire and a home-made (there was no other kind) transformer. (In the first post-war years, just like during the war, electricity was rationed.)

And if he could fix the radio, not to mention a TVЕ I was so embarrassed (at first) to take money for TV repairЕ

How avidly we would wait for every issue of Radio magazine and every installment of the series Radio Library for the Masses! Around 1949 the book УA Hundred Answers to the Questions of TV HamsФ appeared. There were lucid explanations of Уdouble interlacingФ (two-way scanning), and why the knob on TV sets (of the time) were labeled УdistributionФ: it was there simply for adjustment of vertical alignment. But what terminology!

Our Ham Radio movement was driven by the scarcity or outright absence of radio sets, and by the primitive level of radio equipment of that era, built from scavenged parts. Still, a lone radio ham, armed with a soldering iron and parts bought at a flea market, could compete with industry in building prototypes.

In our time of consumer abundance and TV sets based on a sole mysterious microchip, this sort of radio ham activity would be impossible.

I somehow regret thisЕ

I am probably very lucky that my childhood happened during the romantic period when radio technology was first being developed, and my mature years Ц in the romantic beginnings of capitalism and entrepreneurship in Russia.