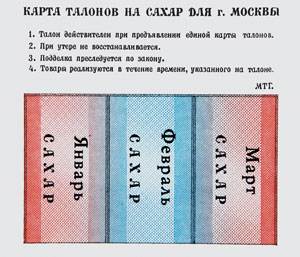

We had not yet reached the level of outright hunger, but we were beginning to ask ourselves what we would have on the table the next day. This kind of atmosphere lends itself to deep thoughts on finding ways to survive. Besides, we’d had it with working for the military and being at the mercy of the ever-watchful security services. We wanted our own business.

My colleague Igor Kaplun and I spotted somewhere in Leningrad a good Soviet business name, KB Impulse, and borrowed it for our company; we needed something to help disguise that we were going private, which would be repugnant to the average, and not so average, Soviet citizen.

I had a telling conversation with one of the people from the second floor at RTI were the security services and military reps were stationed.

“So what ministry will your KB Impulse belong to?”

“None.”

“That cannot be. It’s impossible.”

One of our first commercial products was a car radar detector, which we licensed to our production plant in Kuntsevo. Designed by Yevgeniy Sedenkov, the detector sold pretty well in stores, but naturally, it wasn’t going to sell enough to ensure the success of either the plant or our company.

One of our first commercial products was a car radar detector, which we licensed to our production plant in Kuntsevo. Designed by Yevgeniy Sedenkov, the detector sold pretty well in stores, but naturally, it wasn’t going to sell enough to ensure the success of either the plant or our company.

Our other products were satellite and cable TV equipment. Unfortunately I don’t have any photographs of them. These products were being produced at two plants at once, where management, just like us, didn’t have any marketing skills. The satellite TV system was on sale for a time at the Ether store on Gorky Street.

Our other products were satellite and cable TV equipment. Unfortunately I don’t have any photographs of them. These products were being produced at two plants at once, where management, just like us, didn’t have any marketing skills. The satellite TV system was on sale for a time at the Ether store on Gorky Street.

There was no serious market for these products back then, and the licensing fee the manufacturing plant paid didn’t make us rich either.

During Soviet times, CNPO (acronym for Central Scientific Production Conglomerate) Vympel was one of the largest structures in the military-industrial complex charged with creation of an anti-missile defense.

Here is a memento of that era, the RTI order which I myself prepared.

Completely nonsensical negotiations and mutual presentations (there, I just used a term that we would never use back then), going on for almost a week, were leading nowhere. Nevertheless this episode was to be of great significance:

- Foreigners were allowed on the grounds of RTI;

- Our team got interested in cellular communications;

- The negotiations took place in the offices (room 404 in the official order) of the former Party Committee, which later on became the home and the headquarters of VympelCom.

The Party Committee… Whole three rooms… The first years of VympelCom…

In the first room sits Valery Goldin, among others, at his desk piled high with papers (we, and not only we, practically didn’t have any computers at the time!). The door to the left, marked “Party Committee Secretary,” but now yours truly, the president of VympelCom sits at his desk. Note the curious detail: as I said, I’ve never been a member of the Party, but my wife was not only a member of the CPSU, but to boot the secretary of the Party Committee of the Institute of Archeology at the USSR Academy of Science. When RTI director Victor Sloka found out about it, he saw something either immoral or anti-Soviet in this situation. Just a joke.

VympelCom veterans used to say (or perhaps say even now), that they got their jobs through the Party Committee.

The desire to demonstrate at least something from that Party Committee atmosphere brings me to a later period of time. This photo was taken in 1995 at the signing ceremony of one of our fateful contracts with Ericsson. So, this signing took place at the once famous conference table of the Party Committee of the Radio-Technical Institute of the Soviet Academy of Sciences (the Academy of Sciences affiliation was but a decoy for foreign intelligence; in fact, RTI answered to the Ministry of Radio Industry). And now, sitting at this table after the signing, yours truly is shaking the hand of the Ericsson representative, whose name eludes me. To my right is Georgy Vasilyev. I will have a chance later to say a few words about this wonderful man, as well as about others in this photo. Standing, from left to right: Konstantin Kuzovoi, Valery Goldin, and another man from Ericsson.

On the right the door bears the sign “Union of Young Communist Youth Committee.” Our American partner Augie Fabela occupies it. I will have more to say about him later.

Many years later I saw this sign somewhere in my archive, and have not lost hope of finding it. If I do find it, I will put it up on the door of Augie’s office in our new main building on Krasnoproletarskaya Ulitsa. It is one of the most luxurious offices in one of the most luxurious office buildings in Moscow. And at the end of November, 2007 VympelCom was worth $ 45 billion (!!!). So, there you have it!

Let’s get back to the early history, though…

Or, perhaps, the story of VympelCom began on October 18, 1991, when CNPO Vympel and Plexsys, American company, signed a Letter of Intent.

The Letter announced the creation of two joint ventures: a cell phone equipment producer and a cellular carrier. The “Soviet side” – as referred to in the Letter – was charged with obtaining a license in Moscow for a system that would be profitable and serve no fewer than 600 subscribers.

The new network’s ambitious subscriber target roughly corresponded to the actual number of users of Altai, the country’s radio – not cellular – telephone system, installed in the cars of the power elite in Moscow and its environs. The radio telephone antenna on the hood of a car immediately broadcast the occupant’s important status.

Incidentally, in the course of privatization of the Moscow city telephone network, the Altai system was acquired by a famous woman (among the telecom crowd), Asya Petrovna Ositis, who was also the owner of the company ASVT.

A couple of years later, Asya Petrovna turned out to be our main competitor: we were both seeking the AMPS cellular network license for Moscow. At the Moscow government bidding commission, in the office of Korsak, the head of the Department of Transportation and Communications, one of the main arguments that Asya Petrovna used was that she owned a well-equipped garage which could be used to install radio telephones in automobiles. The news that cell phones could be carried in one’s pocket was met with distrust in certain circles (our first phones did require a big pocket, but not a car trunk).

The range of possibilities of the cellular equipment produced by Plexsys corresponded to about 600 subscribers.

Yes, and I forgot to mention that the American company could have delivered cellular telephone equipment for the American AMPS network, but the Letter of Intent prescribed the use of a NMT-450 network in Russia. And to think that the Americans, together with us, were ready to start producing and distributing equipment for this band all around the globe! (That’s how it was put in the protocol. Goes without saying, it was baloney).

The American AMPS standard, exotic for Europe at the time, began to figure in our plans a little later.

A couple of words about the companies that signed this Letter of Intent:

At the time of our meeting, about one hundred thousand people were working for CNPO Vympel, which was state-run, while Plexsys, a private company, employed less than a hundred. The first AMPS networks operating in Russia, and in Moscow in particular, used Plexsys equipment. Soon we switched to the digital version, DAMPS, with Ericsson supplying the equipment (just this one little phrase reminds me of several funny, sometimes dramatic stories, but I don’t have enough energy or talent to tell them here).